This is the eighth in a series of posts describing my transition from young earth creationist to theistic evolutionist. In the first post, I described how Alan Roxburgh's 5-phase description of paradigm change describes this transition well, and I have been using his framework to shape this discussion. See the introduction for a list of all the posts in this series.

This is a continuation of the previous post. In the last few posts, I described how the religion of my youth had taught me that science was the enemy of faith. I was taught to believe that evolution was an evil idea invented by Satan to lead people into atheism. It was beginning to look like they were right. I had discovered the overwhelming evidence for the truth of evolution, and was terrified of the implications. If evolution was true, then my faith in God must be a silly case of wishful thinking.

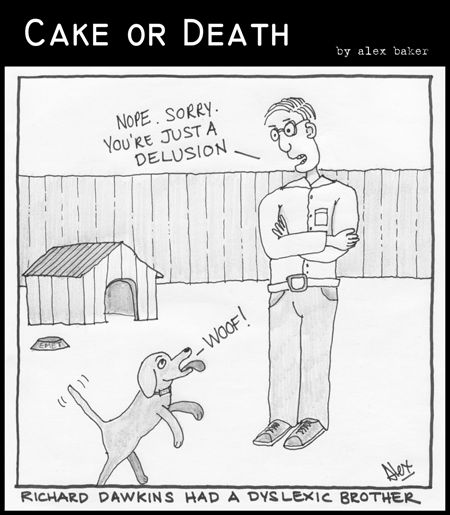

The fourth phase in Roxburgh's description of paradigm change is that of transition. The first part of my transition phase involved dealing with atheist arguments that had caused my faith to diminish to a tiny ember. In my last post, I discussed two of the main ideas that helped me deal with atheism. In this post I'll discuss what I see to be the main flaw in atheist Richard Dawkins' view of God, and then deal with a problem I mentioned in a previous post about the lack of evidence for God's action in the world.

3. Dawkins' picture of “god” is naturalistic, not supernatural

One thing that strikes me as I read Dawkins' anti-religious writings is that Dawkins seems to be completely stuck with a picture of a god that is totally within nature. I didn't notice it in my first reading of The God Delusion, but it becomes more obvious to me every time I read or hear him speak. This was an important element of my transition; I deliberately approached subjects that I had a one-sided knowledge of and balanced out my familiarity with both sides of each argument.

As I said; Dawkins's view of god seems to be that of a god who is within nature. This is important, because almost every one of his scientific arguments against the existence of God assumes a god that is within nature. It is easy to see why: a God outside of nature is not within the purview of science.

Take this quote from Dawkins in this debate with Alister McGrath; notice how he constantly invokes the “probability” of God's existence:

"When you say god didn't come into existence but was always there, I find that not really very helpful because suppose I go back to my problem of explaining the eye; it would be no kind of answer to say "oh, well the eye was always there", it would still be something that requires explanation in the sense that anything statistically improbable does. So I don't think you can't get away with it with an eye, and I don't really see why you can get away with it with God." [21:14]

And just a few minutes later:

“Everybody agrees intuitively that the eye is far too improbable to have suddenly jumped into existence, and I want to say the same about God, and you don't and I don't understand why not...”

An eternal, supernatural God doesn't make sense to Dawkins, because for him, everything must be explained naturally. This can be seen by his insistence on comparing God with an eye: He requires the same kind of (scientific) explanation for God that he requires for an eye. He sums up this belief quite succinctly when he states:

“Any entity, any being, capable of designing a universe, or an eye, or a knee, would have to be the kind of entity which would be statistically improbable in the same kind of way as the eye is.” (emphasis mine)

This is a classic case of begging the question:

1) It's very improbable for natural causes to give rise to a being capable of creating the universe.

2) Therefore, God does not exist.

Dawkins' implicit assumption is that any god must exist within nature. He then bases the rest of his argument on this assumption. This is circular reasoning and complete nonsense. The Christian God exists outside of nature, and therefore it is nonsense to speak of the probability of His existence. The god that Dawkins argues against has nothing in common with the Christian God.

4. Divine Action: God as “The Great Delegator?”

In a previous post I mentioned one of the most significant challenges to my faith is the difficulty I experience in perceiving God's action in my life. This is a problem I still struggle with today, but McGrath provided me with some insights that help the situation considerably.

For instance, in the same interview I mention above, McGrath discusses this matter with Richard Dawkins. When discussing God's part in the September 11 terrorist attacks, McGrath states:

"Why didn't God just take the steering wheel [of the terrorist's plane] and change things? Well, that has been a constant issue down the ages as you well know. Christians understand God to have made the world in a certain way that is like a framework, but does not actually intervene. Of course the classic example of this the crucifixion. People were screaming at Jesus: 'If there is a God, why doesn't he just take you away from here?' That reminds us that we are dealing with a God that does not intervene directly in the world as we might hope." [47:40]

So God apparently prefers to delegate his action to creation itself; His activity in the world happens almost exclusively through natural causes. I didn't quite grasp this concept while I was initially dealing with the atheist proposition, but later it resonated with me because it fit perfectly with my experience. The concept of God as “The Great Delegator” sowed the seeds that eventually grew into an understanding of a God who is constantly creating through natural processes (evolution). This concept was simultaneously a defense against atheism and an introduction to the God who created evolution.

Unfortunately, this problem is not completely solved. A God who delegates His action to his creation can explain the lack of His obvious action in our world. But most Christians, including McGrath, claim that God does intervene in the world. In their discussion, McGrath states that if one child were spared in a devastating earthquake (while thousands of others perished) God could be seen as intervening to save the child. Dawkins points out the inconsistency of this position:

“What worries me is the inconsistency of what you just said when when I asked you whether God saved that one child... Sometimes you say that God doesn't intervene, (and you make a very eloquent case for why it would be a rather undignified thing to do as a God.) On the other hand you say He does intervene when He rescues one child from a earthquake.”

In a sense Dawkins is saying “Which one is it! Does he intervene or doesn't he?” I think Dawkins has a point here. Sure, God is free and able to intervene in one case and delegate in another, but for us to conveniently invoke God's intervention in this way is a pathetic case of theological cherry-picking. We really don't have a leg to stand on.

I think one possibility for obtaining a consistent picture of God's action centers around the extent of His involvement in the creation of natural laws. The word “design” has undesirable connotations in this context, but bear with me: What if God has so intricately designed the natural laws so as to bring about his purposes in both types of situations? What if God set up natural laws so as to save the child from the earthquake in what only seems like a miraculous way? This suggests a God in control of his creation in a completely different way; the laws of nature truly become the hand of God acting in our lives. It's hard for my finite mind to imagine, but I think this only amplifies the wonder of God and His creation.

So in conclusion: Atheistic ideas had dealt a serious blow to my faith, resulting in a seemingly perpetual state of doubt. With the help of the writings of people like Allister McGrath, I dealt with this problem by first realizing that both atheism and belief in God were faith positions. I decided to choose faith in God, regardless of my feelings about whether or not that faith was real. I saw that atheists like Richard Dawkins presupposed God's non-existence, and this could be seen in their main arguments for their position. Furthermore, my view of God was altered significantly with the observation that He seems to act almost exclusively through natural causes, and these causes could be so intricately designed so as to bring about events that are both mundane and incredible. This matched up well with my every-day experience. Finally, I was left with the resolution that my faith, whatever would become of it, would cease to be real unless it deliberately incorporated all the evidence from all credible sources.

In the next post, I'll continue discussing my transition phase by describing how I dealt with the remains of Young Earth Creationism that still lingered in the corners of my mind.