Dealing with Atheism

As I described in the last few posts, disembedding from my YEC roots was pretty thorough. I had learned a lot about evolution, and was completely convinced of its veracity, despite being taught as a youth that it was an idea invented by the Devil. I believed in an old earth, and and old universe. I was frustrated and confused because I had been taught (and still believed) that Genesis clearly stated that the universe was created in six days.

I had adopted old earth creationism as a sort of stop-gap, but this also crumbled under the weight of new scientific knowledge and devastating atheistic ideas. Suggestions by atheist writers had been devastating to my faith, and I couldn't shake the thought that all my religious beliefs were just a sad case of wishful thinking. Was I just hanging on to God because I would loose my friends, marriage and parent's love?

In Roxbaugh's description of paradigm change, the fourth stage is "Transition". My transition stage involved dealing with four different things: atheism, young earth creationism, the people in my life, and the science-faith conflict. I'll describe how I dealt with each of these in separate posts. Each of these happened simultaneously, but I will discuss them sequentially to avoid total confusion.

Dealing with Atheism

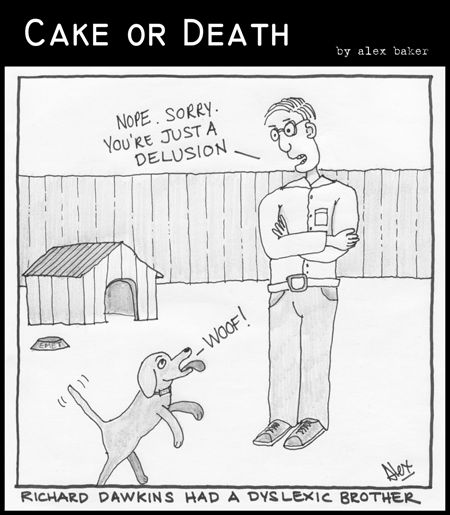

As I mentioned in my previous post, atheist suggestions (particularly those coming from a scientific perspective) had a significant affect on my languishing faith. One of the most outspoken atheists is of course, Richard Dawkins. Young Earth Creationists do a terribly poor job at defending against Dawkins' attacks, resorting to their typical tactics: quote-mining, red herrings, and ignoring Dawkins' actual points. As a result, I was surprised when I encountered the writings of Allister McGrath.

Two of McGrath's books, Doubting and The Dawkins Delusion, were extremely helpful in dealing with atheism. McGrath approaches Dawkins intelligently from a scientific perspective, acknowledging the value that scientific inquiry and reason can have to the conversation.

An even greater help was a debate between McGrath and Dawkins, which can be seen here. Watching this for the first time was rather poignant for me; I was overcome with relief and hope as I watched McGrath engage in an actual conversation instead of the usual circus I had constantly seen from YECs.

An even greater help was a debate between McGrath and Dawkins, which can be seen here. Watching this for the first time was rather poignant for me; I was overcome with relief and hope as I watched McGrath engage in an actual conversation instead of the usual circus I had constantly seen from YECs.I'm going to discuss several main ideas that were extremely helpful in dealing with atheism. Some of these come from McGrath's body of work as a whole, some are more general. I'll give references where I can.

1. The faith of atheism

The main, over-arching problem with atheism, at least for me, is that it is just as much a matter of faith as is any religious faith. Evidence and reason are vital, of course, but at some point the usefulness of evidence and reason come to an end, and we are left with a choice. McGrath describes this in Doubting:

“[W]hen anyone starts making statements about the meaning of life, the existence of God or whether there is life after death, they are making statements of faith. You can't prove, either by rational argument or by scientific investigation, what life is all about. Whether you are Christian or atheist, you share the same problem.” Doubting, p.34

McGrath goes on to explain that doubt is not something that only Christians are vulnerable to: Atheists themselves are in the same situation. They doubt too.

It really came down to a choice: Would I have faith that God exists and wants a relationship with me, or would I choose to have faith that He does not exist? A third option, to continue to dwell in indecision, was also possible. But I had wallowed in indecision for so long. My soul was rotting away, and there wasn't much left.

At one point I read Phillip Yancey's book, Disappointment with God. While I wouldn't recommended it to anyone in a similar situation, it did make this point very clear to me. I had to choose. In his book, Yancey quotes Thomas Merton on the importance of this choice:

"How shall we begin to know who You are if we do not begin ourselves to be something of what You are?" asks Thomas Merton. "We receive enlightenment only in proportion as we give ourselves more and more completely to God by humble submission and love. We do not first see, then act: we act, then see. . . And that is why the man who waits to see clearly, before he will believe, never starts on the journey."

I definitely did not see clearly, and this is why I was finding it hard to act. God was not real to me, and previous efforts to change this had proven futile. But it was clear to me that I needed to make a choice, and act on that choice. At that time, this was all the farther I took this idea.

As of the moment I write this, I am still discovering what that all means, but I do know that Merton was right. He suggests that the more completely we give ourselves to God, the more real he will become to us. In a way, this is blatantly obvious. But it's also a strange way for God to convert new believers, isn't it? I think it shows just what kind of people with whom God wants a relationship. And it reveals a little bit of His character; he seems to want us to come to him on our own accord; He will not impress us or bully us into a relationship. In a way, He's kind of shy.

Note: I've discussed the subject of God's silence in a previous post.

2. Making sense of things

McGrath makes another suggestion that became quite important to me. He suggests that one of the basic goals of faith is to try to make the most sense of things; to try to explain our experiences and convictions in the most complete and internally consistent way possible.

This concept may sound strange, depending on ones religious background. It sure sounded foreign to me at first. I had been raised to be content with mysteries and unknowns, so burdening religious experience with the task of explaining “everything” sounded almost sacrilegious. But I think this is right at a very basic level. Deciding that God definitely doesn't exist would solve some of the problems I had been struggling with, but leaves others open and unsolved. (I do exist, after all...) Faith, (especially Christianity) attempts to answer more of these questions more consistently.

McGrath, (in his debate with Dawkins) when discussing whether faith is rational, says:

"Evidence takes us thus far, but then when it comes to deciding between a number of competing explanations, it is extremely difficult to have an evidence driven argument for those final stages. I believe faith is rational in the sense that it tries to make the best possible sense of things. But in the end it has to move beyond that, saying: Even though we believe this is the best way of making sense of things, we can't actually prove this is the case.” (at 4:58)

So an element of faith is the process of dealing with the evidence, and trying to make sense of it all. This appealed to me, since the religion I grew up with had completely ignored (intentionally or not) a lot of the evidence. I was at a point where any faith I chose to act upon must include (and integrate) all the evidence. ALL the evidence.

These are just a couple of the main ideas that helped me deal with atheism. In the next post I'll discuss two final ideas that helped increase my doubts about the faith of atheism, and enabled me to make a choice to pursue a faith that incorporates all the evidence.